This article was published at Transitions Online and we publish it here with permission by Transitions Online.

A Quality of Silence

by Michael Church

26 November 2002

On the trail of Armenia’s richly kaleidoscopic music scene.

Getting a grip on Armenian culture is notoriously hard, given that more Armenians live outside the country’s borders than within them. Those borders themselves–which once reached far beyond the modern state into what is now Turkey and Iran–have themselves dramatically contracted. Driving into Armenia from Georgia, you leave fields of intense green for a landscape of dry rocks. Walking down the pink-stone central boulevard of Yerevan–holiday haunt of the Soviets–you wonder where the crowds have gone. Looking up at snow-capped Mount Ararat, whose mirage-like presence adorns every restaurant wall, you remember it’s in hostile Turkey. Seeing the Holocaust monument–a dagger piercing the sky–you try to imagine the 1.5 million Armenians whose deaths it commemorates. For a national capital, Yerevan itself is astonishingly quiet.

I found his choral music–folk melodies so deftly arranged that the raw beauty of the originals simply glows the more brightly–in a rehearsal of the Armenian Chamber Choir, whose members were quite unfazed by the honking traffic all around their drafty hall. No other choir sings this music with such passion and precision. I also caught orchestral arrangements of Komitas’ work with the National Chamber Orchestra, whose director Aram Gharabekian–a diaspora Armenian brought up in America–referred me back to that great unnatural silence.

“When I first came to Armenia in 1992,” he said, “there was deep snow, no electricity, no food, no petrol, everyone went about on foot. But I felt this deep vibration: Armenians are very noisy people, yet underneath there was this stillness, a profound silence that seemed to come out of the earth, the thing you feel most obviously when you visit a monastery.” This silence, he said, was the essence of music: “The silence which exists just before music begins, and which is there just after it has ended. The quality of that silence tells you what music has done to you, and for you.” To prove his point, one track on the orchestra’s latest CD is 40 seconds of silence, recorded at the country’s oldest monastery.

Aram Khatchaturian’s ghost hovers benignly over the house he was given by his grateful Soviet masters, and which is now his museum. The fact that this great symphonist was born in Tbilisi makes no difference, since in 1903 the Georgian capital was in musical terms an outpost of greater Armenia. Meanwhile, his music is played at concerts all over town: One of these was by the Armenian Philharmonic, whose manager, Nika Babayan, described the plight in which orchestral players now find themselves. “When the Soviet system collapsed, so did state support for music. Armenian musicians were pitched into the international market economy, without being prepared for it in any way. We knew nothing about the music business, we had no impresarios, no international contacts. We had to start from zero, which gave us huge problems.”

Gharabekian’s story reinforces that point. “When I was invited to direct the chamber orchestra, I accepted because I knew the great potential of Armenian musicians, and I knew it was possible to create an orchestra of international stature. But the minister of culture warned me that I’d be starting from scratch, that he didn’t have anything to give me–all he could give me was his blessing, and carte blanche to do what I wanted. I knew it was going to be tough, but I wasn’t prepared for how tough. I’ll never forget my first meeting with my secretary–outside in the square, as we didn’t have an office. I asked her to take notes, and she blushed and said she didn’t have any paper. The players didn’t even have music stands.” In its first year and a half, the orchestra was minimally financed only by the state, but when the London-based Manoukian Foundation decided to fund it, its musicians became overnight the highest-paid in Armenia. Even so, they still augment their pay by teaching, and by playing at funerals and weddings.

Most musicians’ salaries are shockingly low. Philharmonic players earn on average $150 per month, but players in the Opera House orchestra get a mere $20–and with modest one-room flats in Yerevan renting for more than twice that amount, all have to take at least one other job as well. “You want to know how we survive?” asked Babayan. “The diaspora! I have a brother and sister working in Moscow, and if I didn’t have this job they would simply support me. Almost every Armenian family has members living abroad, who systematically send them money. This is how the country has survived ever since the great exodus of 1915.”

AT EASE WITH ARPEGGIOS AND ASHUG

But the end-of-term summer concert at Music School No. 2, which is named after Sayat Nova–the 18th-century bard who is Armenia’s musical patron saint–suggested that the Soviet music-education system is still alive and well. One after another, the 7-, 8-, and 9-year-olds walked up and did their stuff before being bombarded with flowers: mostly strings, not all budding virtuosi, but all with immense character and individuality to their playing. This junior music school owes its continuing excellence to the violin guru who heads it, but Petros Haykazian is nearing retirement age and has no obvious successor. As Babayan sadly points out, Armenia’s best musicians now routinely emigrate after graduation from the conservatory: “Our salaries are too low, and our market is too small.” There’s a void looming ahead.

At the parallel Sayat Nova school for ashug song–the art with which this great singer once beguiled the Persian court–there was another end-of-term concert. The boys’ voices had scarcely broken, but they’d already got the authentic feel of this Arabic style and the ecstatic gestures that go with it. Then, in the austere chants of Mass at Etchmiadzin the next morning, I spotted the best of those boys singing his heart out. Such a sight could only surprise someone accustomed to the West’s rigid musical divides.

It’s greatly to the conservatory’s credit that, despite the prevailing excellence in Western classical music, traditional music is taken extremely seriously there. Two of the student ashug singers I heard had the sort of artistry that, given the right backing, could propel them to international stardom: listen for Susan Khanamirian and Karen Avetisyan. I also caught some ace players on the duduk: it’s time the world realized that Djivan Gasparian is by no means the only weaver of mournful spells on this deceptively simple double-reed flute, whose origins go back 3,000 years.

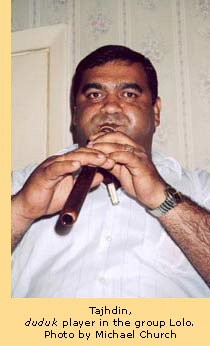

Armenia may not be on speaking terms with its hostile neighbors to the east and west, but it’s the only state in West Asia that doesn’t harass its Kurds. A tortuous search led me to a three-man Kurdish group called Lolo, who kept their assignation with me in a back street, but then did their best to talk themselves out of a job. Tajhdin, the duduk-player, waved his forearms–hugely swollen after an accident at work, so no, he couldn’t possibly play. Jimo, the flutist, named an impossible fee for a 30-minute session, and when I demurred, stomped off round a corner saying he had better-paid work elsewhere. Reza, the singer, just looked helpless. Let’s call it a day, said my weary interpreter.

I suggested, as a last resort, that we try them with half that impossible fee, whereupon Jimo miraculously rematerialized, made a noisy show of outrage, and accepted. We followed them to Jimo’s lair in a broken-down building outside town. Reza asked for vodka “to oil my throat,” and they then embarked on one of the dizziest musical hours I’ve ever experienced. “Hope we’ll hear you in London one day soon,” I said as we took our vodka-tearful leave, and Reza rolled his eyes humbly to heaven. Is there an impresario in the house?

A young pupil at the Sayat Nova music school.

A young pupil at the Sayat Nova music school.

Photo by Michael Church

My aim was to take a musical snapshot of this city: I had a stereo mike, a DAT recorder, and seven days. I also had some encouraging facts: the growing number of kids queuing to study at Yerevan’s music schools and the increasing international success of those schools’ graduates. There was troubadour music called ashug to pursue, and two composers to track down: Aram Khatchaturian, whom everyone has heard of and whose centenary celebrations are nearly upon us; and a more significant composer, whom almost no one outside Armenia has heard of, but whose fate encapsulates that of his country–Komitas.

Orphaned Solomon Solomonian took the name Komitas–after a seventh-century hymn composer–on being ordained a celibate priest at Etchmiadzin, Armenia’s holiest church. He had a fabulous voice, but his passion was for the voices of others: pre-empting Bartok by 30 years, he collected folk songs in villages round Ararat, and applying Western techniques created ravishing harmonies. In 1915, with 700 other Armenian intellectuals, he was seized and tortured by the Turks; he escaped alive, but the experience drove him mad, and he died in a Paris asylum 20 years later.

Michael Church is a writer and broadcaster specializing in music. He is a columnist for BBC Music Magazine and a roving reporter for the BBC World Service.

Copyright © 2003

Transitions Online

All rights reserved.

Chlumova 22, 130 00 Praha 3, Czech Republic,

Tel.: (420) 222 780 805, Fax: (420) 222 780 804.

E-mail: transitions@tol.cz